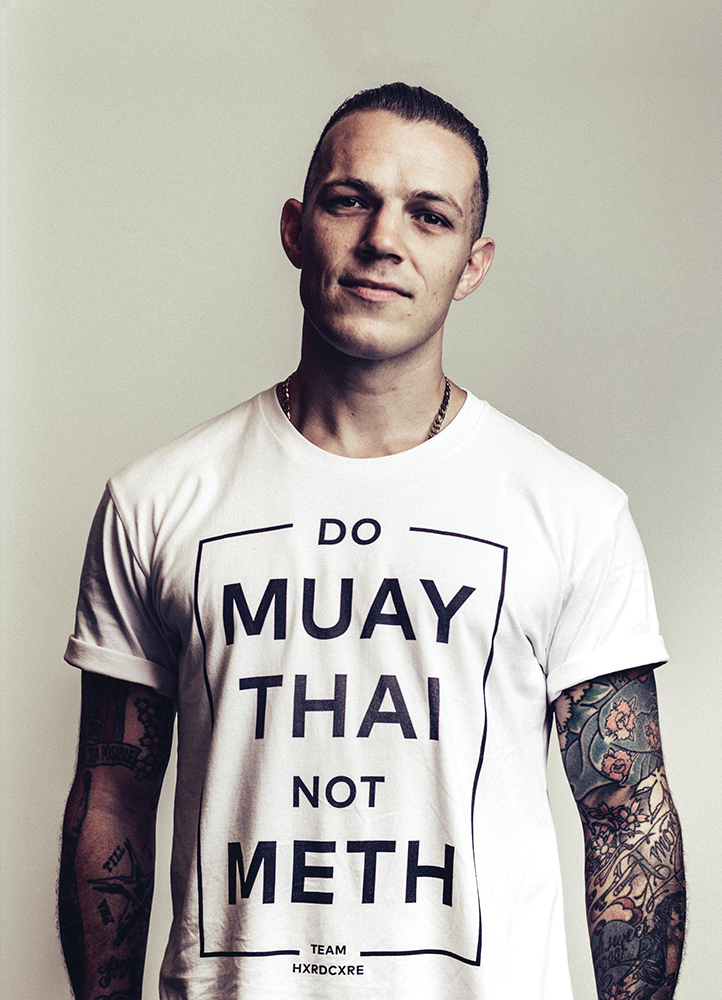

Photo Credit Damian Alexander.

A Muay Thai fighter, social activist, and public speaker, Richie Hardcore has gone from fighting in the ring to fighting for social justice. Verve chatted to Richie about the work he does, the issues he sees New Zealand facing, and how he keeps on top of his mental health and wellbeing.

Firstly, where does the name Hardcore come from?

I legally changed my name to Hardcore when I was kickboxing, it was my ring name. Hardcore is a sub-genre of the punk rock scenes which emerged in America in the late ’80s. It had an undertone of politicisation and trying to fix things. It had themes of veganism and environmental protection, and for me I found songs about feminism, which gave me something to be angry against and helped me understand the world I lived in a lot. It changed me a whole lot.

What areas do you work in?

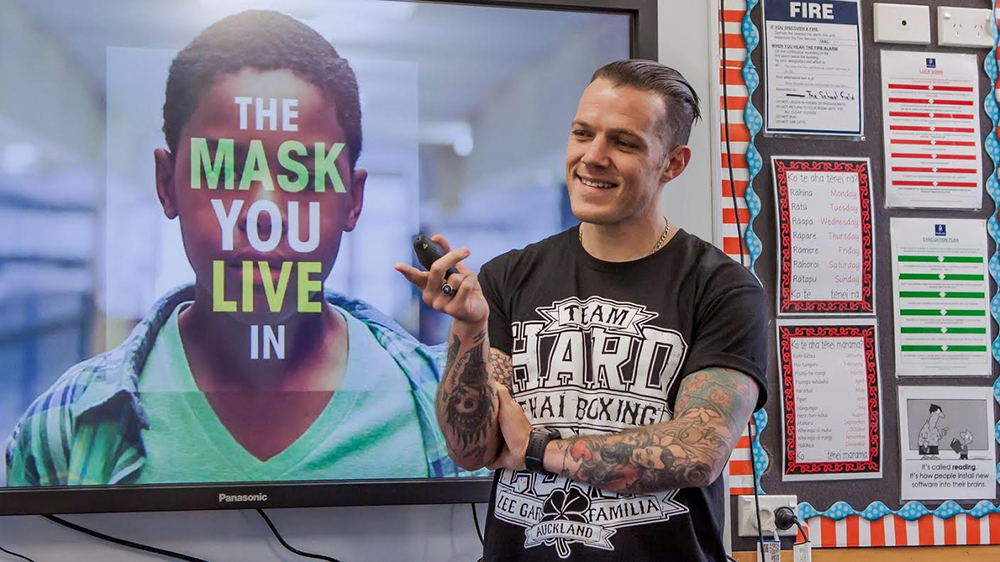

I’ve organically become a public speaker and educator, without really meaning to. I did some work for the Ministry of Health in reducing alcohol and drug harm reduction for five or six years, and within that we started looking at sexual violence as an alcohol related harm and then at sex and consent within university scopes. After that, Rape Prevention Education asked me to become a board member for them. People then started inviting me to speak, I was nominated to be an ambassador and then a board member for White Ribbon, and I do some work for the Ministry of Social Development with their ‘It’s not okay’ anti-family violence campaign.

But then more and more people were asking me to speak privately, like schools and universities, so I’ve become an educator, just going where I’m asked to be. I’m always trying to keep up with research and academia because all the stuff I’m talking about is evidence-based approaches to violence prevention.

I’m always trying to help people form critical filters. A lot of the media and messages we’re exposed to are misogynistic, and violent, and super unrealistic. Young people who don’t have these critical understandings aren’t able to do this. It’s not about censoring things, but it’s about helping people to learn that there are other ways to think and behave.

The best feedback I get is when teenagers find my Instagram account and message me and say I’d never thought about things this way, thank you very much. That is really rewarding to me.

Through the work you do in the mental health area, what do you think are some of the biggest factors that make it such a big issue in New Zealand?

It’s a really multi-faceted issue. After being invited by Mike King to talk on the radio about mental health for a couple of years, it has led me to understand a bunch of things. One of those things is that, not for everyone, but for some, depression, anxiety, and other mental health issues stem from trauma, societal causes such as lack of community, fracturing of society, working longer hours, moving less, eating less nutritious food, social media, and excessive alcohol use. We’re moving away from things that actually satisfy us, like human connection, helping other people, and being connected to nature.

There has been a massive increase in the gap between the rich and the poor, there’s structural and institutionalised inequality and discrimination, and an imbalance of power between men and women. So essentially, people don’t feel very good about themselves.

We need more people out there doing work like Mike King. But there are some great government approaches coming out at the moment, such as the 1737 and the Safe To Talk, but these are still the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff.

“We need to let boys know it’s cool to wear pink, you can play with teddies, it’s fine to not feel okay, and it’s okay to cry.”

The work you do often has a lot to do with masculinity and notions of toxic masculinity, what’s your view in this area?

So I just helped out with a body of work as part of the National Council of Women’s new gender equal New Zealand campaign, which conducted a body of research to look at New Zealanders’ attitudes towards gender. It turns out most New Zealanders agree that women can do most things a man can do, yet a large part of New Zealanders still think that boys don’t cry, if you back down from a fight you’re weak, or that it’s not alright for boys to play with dolls. We need to challenge those ideas. When we trap men in roles of expected behaviour, it means that they have no place to go. Which results in violence towards ourselves, mental health issues, and domestic violence. The more men try to fit into perceived masculine norms, the more problematic behaviours they present. So we need to let boys know it’s cool to wear pink, you can play with teddies, it’s fine to not feel okay, and it’s okay to cry.

How do you ensure that your mental health is looked after?

I’ve been to therapists off and on since I was 24. I think that there’s a huge space for talk therapy. It can really help you figure things out about yourself. In the last few years I’ve worked through some really tough stuff in my personal life, and now it’s become more about professional development.

Because of the things I am involved in and talk about, I become subject to a bit of vicarious trauma. I wake up to messages from people about the issues they’re suffering from, abuse they’re being subjected to, among other things, so this can weigh on my mind quite a lot. I sometimes get a bit burnt out from people confiding in me, it takes a lot of mental energy, so I’m learning about how to manage and reserve my mental energy. I have to remind people I’m not a trained counsellor. Sometimes I have to turn people down, which doesn’t feel good, but I do have to look after myself too.

Once in a while I’ll give myself a bit of a digital detox. I use my cell phone a lot which keeps me constantly engaged and in a flight or fight mode. I’ll delete the apps off my phone.

What role does fitness play in your life?

I started competitive martial arts when I was 13 and I’m a Muay Thai coach now, so it’s given me a great pathway through life. I continue to train as part of my overall wellness. I really do love moving my body. When we’re sedentary we don’t really feel good. It’s a hugely important part of who I am, not just what I do.

Some people are really unhappy and unhealthy, but don’t know what to do about it. When we switch what is normal around, like questioning why people aren’t drinking to why they are, why they eat don’t want to eat junk food to why they do, why are you eating a salad to why aren’t you eating salad. We normalise really unhealthy behaviours, which has a real impact on people’s health and lives.

Words: Georgina Shearsby-Roberts

To stay up to date with the with Richie and the work he does, check out the links below:

richiehardcore.co.nz / @richiehardcore / Facebook: Richie Hardcore