Among Aotearoa’s most talented of artists, Kairau ‘Haser’ Bradley is celebrated for blending graffiti with Māori art, crafting distinctive works that pay homage to both his heritage and his artistry.

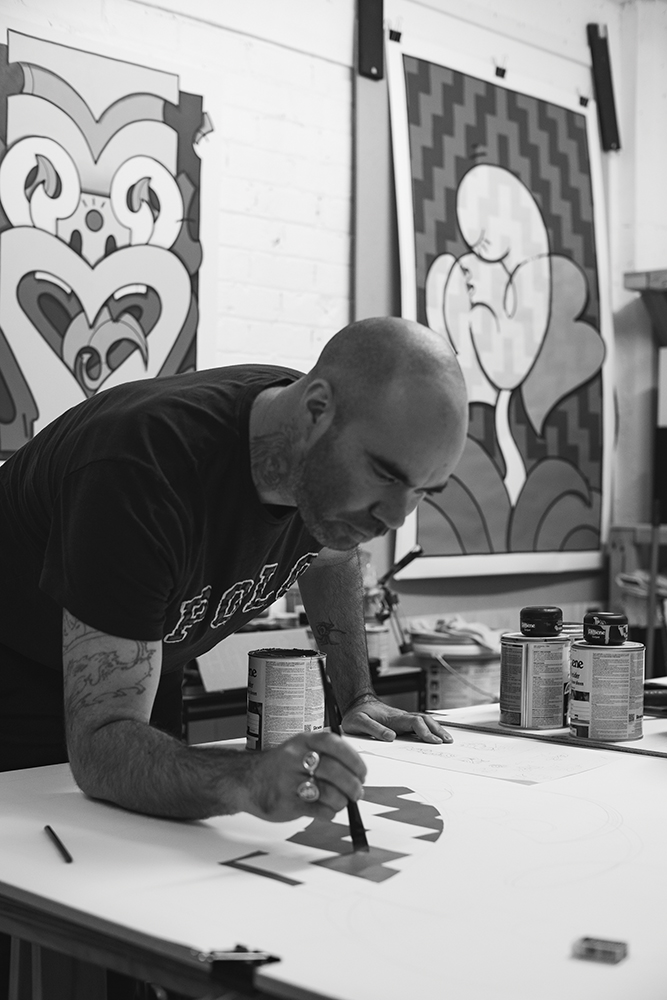

ABOVE PHOTO: Jamie McReady

“I grew up very immersed in Māori culture,” Haser tells Verve. “Whakairo (carving) was one of my dad’s many skillsets, and I was involved in kapahaka for a large portion of my childhood. Like many things, once I found graffiti, everything else in my life took a backseat.”

Raised in Auckland’s western suburbs, the Ngāpuhi artist’s practice reaches from well beyond those early urban canvases to corporate settings and exhibitions throughout Australasia, North America, Asia, Europe, and the UK.

“In 2018, I moved to London, and it was the first time in my life that I thought to myself ‘this is not my home’,” he recalls. “It challenged many of my morals.”

Have you noticed a growing interest in Māori art overseas?

“I think it’s still at a very surface level. Things like the haka and tāmoko are usually how someone will begin a conversation around Māori culture. Visually, orally, and spiritually, it’s such a beautiful culture and you can tell that people want to engage with it, but they are also very cautious around cultural protocols and appropriation, so I take it upon myself to guide them through that process and, from there, point them in the direction of the answers that they seek.

“There is a growing interest and desire to have Māori representation across the globe. It’s very rewarding to see those that have been representing in this space for generations finally getting the recognition they deserve, as well as shining that same light on the rest of us down here that are waiting for our chance to bloom.”

It is not my intention to be destructive, I just enjoy the adrenaline and the mission that goes into painting graffiti.”

Upon returning to Aotearoa in 2020, Haser “found himself” back home in Pakōtai, where, sitting at the foot of “our Maunga Te Tārai O Rahiri” he told himself: “This is where I am from. This is home.”

It was a moment of self-reckoning that, he says, both caught him by surprise, and “changed my creative journey”. “Because I had spent more than two-thirds of my life immersed in graffiti, exploring the limits and the boundaries of this craft, I didn’t want to put this aside as I introduced Māori motif back into my practice,” continues the artist. “Instead of taking a traditional approach to Māori art, I pushed it through the lens of my graffiti practice. This has allowed me to build a body of work unique to me, that pays homage to both my urban and indigenous backgrounds.”

How has western Auckland informed your work?

“West Auckland certainly has its own DNA that is both visually and stylistically obvious. The nature of west Auckland is embedded in me, and I have always claimed Westie status. West Auckland had its own breed of graffiti writers in the 90s and early 2000s so naturally these were the artists that I looked up to. Before the internet arrived and mixed up our inspiration feed, there were still regional styles that were distinctive to suburbs, cities, and countries. There are still elements that are specific to west Auckland’s take on graffiti that are still present in my work.”

Can you tell us how your Kingsland piece (top image) came to be?

“I was approached by some local business owners who were curating some murals in that space. As soon as I saw the site, I knew exactly what I wanted to paint there. I was already working with a Māori-inspired alphabet and felt that the height and length of the of that wall would fit the letters of Kingsland perfectly. I wanted it to be a tribute and landmark for the residents of Kingsland. It’s in an open lot, so it’s only a matter of time before something is built in front of it, but while it’s there, I want it to be bold.”

Boldness is a theme often associated with Haser’s art – and through its heart you’ll often see traditional shapes such as koru. “The core of my work regarding my Māori-inspired practice is the koru,” he continues. “I try not to look through Māori art like it’s a dictionary that I pull from. Instead, I wait for some of these things to present themself in my work which is usually influenced by the story I’m trying to convey. Recently, patterns like poutama and taniko have made themselves present in my work.”

Though Haser’s father was often “creating and painting”, growing up, the artist says that he was more drawn to sport. “At the age of 11, I got my first glimpse of graffiti. It wasn’t anything glamorous – mostly scribbling my name on walls – but it was exciting.”

Over the following couple of years, Haser’s dedication to his new-found craft became “consuming”, and in 2004 he formed a small graffiti crew with “likeminded artists”.

“Both my brother and I chased professional careers,” he goes on, “mine came in the way of design, while my brother took a traditional workforce approach to become a car painter. After years of dedication to our trades, we both stepped away and pursued fulltime art careers. My brother is now a practising tattooer, moko artist, and muralist. We’ve both evolved and matured, and, where we once saw competition in each other, we now influence each other’s journeys, striving to be the best that we can be.”

Were you regularly in trouble during your early graffiti days?

“I like to think that I was absolutely committed to the culture, and so, of course, there was always going to be some resistance from the law. But I have always been very aware of the consequences that come with this life and have faced them head on. As adolescents, I think that we are less concerned with rules and naturally want to test boundaries so there was a time when I found myself in the presence of the police more often than I wanted to be. It is not my intention to be destructive, I just enjoy the adrenaline and the mission that goes into painting graffiti.”

Though graffiti is a culture that “demands bravado and a callous-like ego”, Haser insists that he still finds it in himself to be “mindful and understanding”: “The cultural practice around manaakitanga is embedded in me. This was hugely influenced by my elders who were always mindful of taking care of our family, our community, and our environment.”

Do you also feel a great sense of responsibility when creating works that depict Māori culture?

“Absolutely. But through the guidance of kōrero and wānanga (deliberation) I’m able to navigate this space with my head held high. My work is not made with the intent to profit, or to say what Māori art is and is not, but an honest journey that I share because I believe that it is important that people have as much opportunity as possible to develop a connection with who they are and where they come from.”

Regarding his studio practice, “which is what usually ends up on a community wall”, the artist says that the most recurring themes are “my fear of love, a place for my people, and my hope for a better world”. I ask Haser if he believes that art should always carry a political or cultural message, and he says that it should simply reflect the artist making it.

“It’s important to note that art should be fun as well,” he adds. “An outlet and a therapeutic exercise to feed our creative minds and free ourselves from our daily routines and frustrations. I speak about cultural and political issues because I see the need for more love and growth in spaces that mean a lot to me. But I also paint graffiti because it keeps me artistically stimulated and excited without having to take a stand.”